Urban Theory and Modelling – Paris 2017 - Reflections on interdisciplinarity

24 Oct 2017LUCAS’ Ben Purvis recently attended the ERC GeoDiverCity International Workshop on “Theories and models of urbanization” at the Institut des Systèmes Complexes in Paris. The workshop brought together academics from a variety of disciplines such as physics, computer science, economics, and geography to engage in discussions relating to urban theories and modelling. Keynotes included talks from Michael Batty, Elsa Arcaute, Fulong Wu, and Michael Storper.

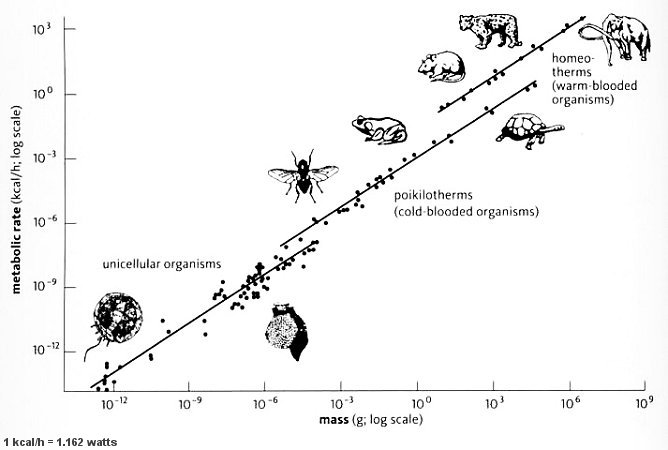

Much of the discussion was focused around hypotheses of scaling laws for urban systems. These ‘laws’ follow from Kleiber’s observation in the 1940s that the metabolic rate of various animals seems to scale with their body mass with an exponent of ¾, i.e. a log-log plot of the two parameters produces a straight line with gradient ¾, as shown in the diagram below. With parallels drawn between urban systems and living organisms, it was natural that urban theory literature would arise considering the scaling of city size with various urban attributes. A key example of this is presented by Bettencourt et al in 2007, with examples of a diverse range of parameters such as new patents, GDP, serious crimes, and length of electrical cables.

Kleiber’s Law, taken from https://universe-review.ca/R10-35-metabolic.htm

These so called scaling laws remain controversial however, Batty explained that whilst there appeared to be a strong correlation, with a non-linear exponent, in rank-size for the largest cities in the US, this correlation became weaker on the inclusion of the not dissimilar cities of Canada. In her keynote, Arcaute presented work that investigated the somewhat arbitrarily defined boundaries of cities, and how changing this definition based upon population density affected the exponent of various scaling laws. This work is presented in a 2016 paper, and provides evidence that urban scaling values are sensitive to the definition of the city.

A recent paper by Leitão et al (2016) argues that least-square fitting is insufficient to conclude the existence of non-linear scaling, presented methodology to better investigate data fluctuations. The existence of non-linear scaling laws was also questioned in a keynote by Marc Barthelemy, who cautions oversimplification of complex reality. Storper too highlighted how they can be useful, but present ‘ever diminishing scientific returns’, as well as arguing how it is problematic to average over huge datasets over many diverse regions and historic time periods.

This contention around the existence of scaling laws seems to lead to more fundamental epistemological questions. Foremost whether universal ‘laws’ that govern the properties of such complex systems as cities exist to be discovered, and whether the pursuit of some sort of ‘unified urban theory’ is misguided. Further there can often be conflation between understanding a system and being able to make predictions, the latter does not necessarily follow the former. Another epistemological conflict arose surrounding ‘measuring of the immeasurable’ and the differences between the quantitative approaches that tend to be taken by physical scientists and the more qualitative interpretative approaches taken within the social sciences.

The value of interdisciplinarity when facing the differing epistemological approaches taken primarily between the physical and social sciences was an underlying subcurrent of the conference. The assumption that there is such a thing as getting the urban system ‘right’ in terms of its physical form was probed by Storper. Disciplinary conflicts were also explored by Lena Sanders, and Isabelle Thomas, who presented the metaphor of ‘lions and butterflies’ for the relation between economists and geographers. Economists being ‘lions’, bound by the rules of the pride, and likely to devour the unwitting economic geographer who attempts to tame them, whereas geographers are more like butterflies freely flying the fields of knowledge and tasting the best of every flower they visit. The stark lack of dialogue between the two fields was explored, backed up with bibliometric work on cross-disciplinary citations. Storper argued the success of economists to produce models of human behaviour (the veracity of these models being immaterial) gives them an edge over the more individualistic qualitative approaches taken by geographers within the broader academic environment.

Perhaps the take home message was, as Michael Storper put it, the importance of being aware and self-critical of one’s own methodological individualism, and it seems this ability may be enriched by discussing different epistemological assumptions in an interdisciplinary environment.